Yang Liqun(front) restores an ancient manuscript as his apprentices observe. Photo: Courtesy of Yunnan Provincial Library

Yang Liqun(front) restores an ancient manuscript as his apprentices observe. Photo: Courtesy of Yunnan Provincial Library

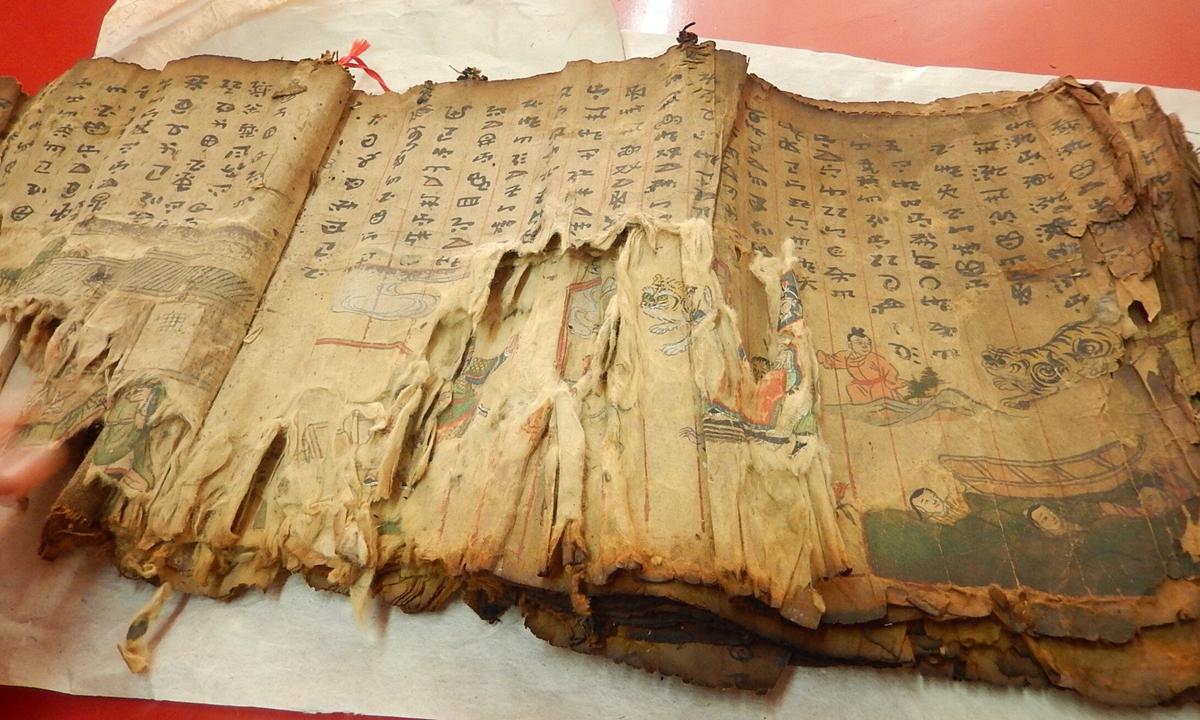

After hundreds of years of being gnawed by insects, covered in mold or burned by fire, a series of ancient manuscripts written in Tibetan have successfully been restored. However, you wouldn’t want to get a paper cut from these books as the paper is made from a special poisonous plant found in the region.

The Global Times recently reached one of the main contributors of the project Yang Liqun, who has been restoring books for more than 50 years by now. Yang is also an important figure in the drive to restore ancient books written in ethnic minority languages in Southwest China’s Yunnan Province, where numerous such ancient books have been found.

Back in 2010, local villagers in Shangri-La, Yunnan, accidentally found thousands of pages of Tibetan Buddhist manuscripts inside a remote mountain cave. News of the discovery quickly spread, attracting the attention of both the local government as well as the Yunnan Ancient Books Protection Center.

“After hundreds of years of suffering, these books were as hard as bricks due to the damp inside the cave. Choosing the right kind of paper for restoration was also a big challenge we had to take,” Yang told the Global Times on Tuesday.

Hidden among harsh mountainous terrain that includes dense bamboo forests and overgrown thorny bushes, the cave is in a high mountain cliff near a village called Nagela, some 140 kilometers northwest of the city of Shangri-La. The mountain’s only connection to the outside world is a single rugged road.

“It was big news at the time. Everyone was curious to learn more about the large collection of Tibetan books that were discovered in a cave,” Yang recalled.

In 2014, the Tibetan manuscripts, which were named after the village, were collected by the center, which organized an expert team to carry out a four-year restoration project. Led by Yang, the center made huge efforts to restore the ancient manuscripts.

After weeks of comparisons and research, the experienced Yang discovered that the paper used in the manuscripts were made from langducao, a poisonous flowering plant found in Southwest China that is used in traditional Chinese medicine. Paper made from this plant tends to be thicker and more resilient than other varieties.

A craftsman told the Global Times that the process of hand-making langducao paper is very complicated, involving at least 12 steps, such as soaking, mashing, and even beating.

The restoration process is equally complicated. The brick-like books needed to be soaked in hot 60 C water for at least a day before they were soft enough to work with.

Digital restoration

The protection center where Yang has worked for more than five decades has succeeded in the restoration of numerous ancient books written in scripts such as the ethnic Yi, Tibetan, Dongba and Dai scripts. The next step is to present these restored ancient works online.

In Yunnan, the provincial library has published copies of extremely valuable ancient books including the Buddhist work Compass for Protecting the State and one of the five most valuable Buddhist books in the Tripitaka. In South China’s Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, 38 restored ancient ethnic minority books have been scanned into an online library so that curious netizens can check them out.

Digitalization can be an extremely difficult and time-consuming process as it requires experts to enter each word by hand into a computer.

In order to more efficiently digitize the tens of thousands of words written in these ancient books into digital form, Wu Yuanfeng, a researcher at the First Historical Archives of China, developed a Manchu script recognition software. Using this software, a 130,000-word memorial written in the Manchu by a Chinese emperor was digitized in just two years.

“Otherwise it would have taken 10 people about eight years to complete if it was typed by hand,” said Wu.

“As long as I can remember, I have seen my father repair ancient books. Those rotten and burnt books could be handled really well by my father,” Yang’s daughter said in an interview.

“As I grew up, I gradually realized the value of my father’s persistence in his career. Now I am also engaged in this business because I want to be just like him.”

In order to attract more participants, the center began to hold ancient book restoration training courses in 2009. As a restoration specialist, Yang was hired again as a teacher despite his retirement years ago. Yet after years of teaching countless trainees, only less than 10 trainees have stayed on at the center to make book restoration their career.

Yang expressed his wish that more young people can join this endeavor.

“It would be a pity if these national treasures were lost.”

More Stories

Indulge in Luxury: High-End Women’s Cardigans Worth It

History of the Computer – Cooling, Part 1 of 2

The Importance of Video and Computer Games